A Turning Point for Italian Fascism, 1920-1921

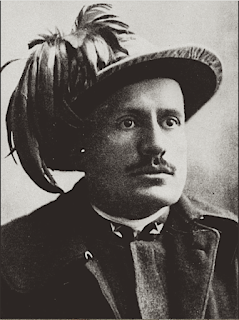

|

| Mussolini as duce. |

Apparently there is a growing nostalgia for Benito Mussolini in Italy. What's the harm, you ask. Why not turn Benito into a cuddly stuffed doll, something you picked up at an amusement park, after you recovered from the roller coaster ride? Put him on the shelf next to your teddy bear.

The desire to sand off the rough edges of history is understandable. We are all masters of self-justification, both as individuals and as nations. But there is a difference between history as it was, and history as you would have it be.

People can lose track of that distinction, saying things that attempt to normalize the abnormal. "He made the trains run on time." "He drained the Pontine marshes." "He built the autostrade." "We didn't have to lock our doors at night." Nothing uncuddly there.

The same Mussolini seized power by violence and lies, erected the first state to call itself totalitarian, engaged in a reign of terror that lasted decades, and ruined his country in a war he never should have fought. Among other things.

Paul Corner has written a whole book exploding the myths of Mussolini nostalgia: Mussolini in Myth and Memory (2022). Corner, currently professor emeritus at the University of Siena, has spent his career studying Mussolini and fascism. His doctoral dissertation at Oxford became a book in 1975. It's called Fascism in Ferrara 1915-1925; my son found it at one of his favorite used book stores and gave it to me as a holiday present. And from there I found his most recent tome.

I'm not sure which of these books has affected me more, and it's probably a silly question to ask, because they both motivated me to write the story you're reading, which will try to make two main points.

First, the fascist rise to power was based on the lie that they cared about the people and were trying to help them. Lying, as we know, has an addictive quality. Once you start, it's very easy to just keep going, and the fascists of Italy certainly did that.

Second, the lies have lived on and are dangerous to this day. Democracy around the world is under attack, with many people looking wistfully for what used to be called The Man on Horseback, wielding power decisively and thereby giving us a better life - because of course there is no downside to dictatorship.

Before we get to Ferrara, let's have a look at broader developments in Italy during the immediate aftermath of World War I (known to Italians as the dopoguerra, or after the war.)

A Look at the Dopoguerra

The time immediately after World War I was a very good time for socialists in Italy, particularly in the north. In fact, the two years 1919 and 1920 are often called the biennio rosso, or two red years.

World War I had been a disaster for Italy. The postwar period was marked by an economic slump, high inflation, and an increasing sense that the existing government was not up to the job.

It's customary at this point to talk about frustration with the final territorial settlement at the peace conference in Paris, which gave the Italians a lot but not everything they wanted. This outcome was called the vittoria mutilata, or mutilated victory. (For a clear and succinct discussion of the postwar situation, see Stanley G. Payne, A History of Fascism 1914-1945, 1995, pp. 87-89.)

I'd rather talk about the incompetence of the Italian officer corps, which had its signature moment in 1917 at the Battle of Caporetto, when Austrian and German troops pushed the Italian army back 150 kilometers, to the Piave River.

Caporetto led 350,000 Italian soldiers to desert. I'd call this a pretty impressive vote of no confidence. To give you an idea of the magnitude of this vote, Italy's entire population at the time was about 37 million - a little more than ten percent of the current population of the United States. If a similar event were to occur in the United States, we would have more than 3 million deserters.

The socialists initially focused their organizing on cities and industrial workers, using the strike as their primary tool. This effort reached its peak with the "occupation of the factories" in northern Italy in 1920, but the occupation fizzled out by the end of the year. (See Payne, pp. 93-94.)

There are a number of theories as to why what looks like a general strike failed. I think a basic cause is that militant action by labor unions failed to inspire any significant action in the political sphere.

In discussing an April 1920 action in Turin, Antonio Gramsci has this to say: "The elements of the party leadership always refused to take the initiative of a revolutionary action, unless there was established a plan of coordinated action, but they never did anything to prepare and develop this plan." (To see the complete article, click here.)

Meanwhile, however, a significant innovation occurred in the rural areas of the Po valley: the socialists, whose organizing generally focused on factory workers, had great success in organizing farm workers. Let's see how this played out in Ferrara.

Spotlight on Ferrara

The socialists had actually been organizing in the countryside for a very long time. In Ferrara, a province located in the Po river valley near the Adriatic sea, socialist leagues of farm workers were first formed in 1901. For workers in rural areas, these leagues were often the only effective political and economic organizations available. (See Corner, Ferrara, pp. 9, 63.) Their time in the sun, however, did not come until after World War I.

Shortly before the breakout of the war, the socialists finally discovered the key to their success - a monopoly on the hiring process. Their tool would be what we would call union hiring halls (they called them uffici di collocamento), and the goal was to require the landowners to hire through the hall. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 15.)

In Ferrara, the socialists pursued economic and political power simultaneously, and their first landmark victory came in the political sphere, with the election of November 1919, in which they experienced a blowout victory. In Ferrara province, the socialists got 43,726 votes; all other parties got a total of 14,299 votes. As Corner notes, "Paramount in the political field, the socialists were soon to occupy the same position in the economic sphere." (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 74, 86.)

Much has been made of the fact that the socialists were perfectly willing to use violence to enforce their will. As someone who is personally dedicated to nonviolence, I have difficulty achieving the historian's desired objectivity here. But I do know that the socialists of Italy in 1920 were not Quakers, and that Gandhi was still in the early stages of his preeminent career in nonviolence.

The socialists used three primary tools to enforce their will - the strike, the fine, and the boycott. A non-compliant person - a strikebreaker for instance - would get a fine, and if the fine was not paid there would be a boycott. If the boycott didn't work, there would be property damage; haystacks would be burned, and animals maimed. If that didn't work, the person could be severely beaten and might die. Deaths were rare, but they did occur. (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 96-99.)

On February 24, 1920, the agricultural workers went on strike, just at the time for planting of two major crops, hemp and sugar beets. On March 6, the landowners folded, acceding to all demands, including increased pay. Above all, they gave the socialists their long-sought monopoly on hiring. (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 88-89.)

With a successful strike and a spectacular contract, it might be reasonable to assume that the level of violence in the province would decline. However, this did not happen. Why? It was a very turbulent time, and there were a lot of angry men accustomed to settling conflict by force. And there is the payback factor. As Corner puts it, "Many years of deprivation and exploitation were not readily forgotten, even in the year when conditions became better." (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 95-97.)

Many people were convinced that Ferrara was in a pre-revolutionary situation (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 93-95), and I'm inclined to agree with them. It's also true that getting a contract and enforcing compliance are two separate things, and the increase in violence in the summer months centered on getting people to abandon their old ways and adopt the new. It wasn't pretty, and there were gun battles, with people wounded and some dying. (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 96-98.)

As all this was going on, the leadership of the socialist party appeared effectively paralyzed, and the landowners were clearly getting their feet under them. All of this can be seen as a replay of what happened in the factories, with the strike in Turin being broken back in the spring, and the whole "occupation of the factories" movement petering out by the end of the year. There's an old army saying: Lead, follow, or get out of the way. The socialist leadership did none of these things. (See Corner, Ferrara, pp. 100-103.)

However, "If the summer of 1920 had seen many socialists confused and demoralized, the autumn found them more determined." In the communal administrative elections of October 1920, the Ferrarese held their ground and even made gains. The socialists had never controlled the commune (or town) of Ferrara, which was the capital of Ferrara province. In this election the socialists won the town in a landslide - 13,000 votes for the socialists versus a total of 7,000 for the opposition. And, as Corner notes, "Provincial and all other communal administrations remained in socialist hands." (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 104, 107, 111. See also Lawrence Squeri, "The Italian Local Elections of 1920 and the Outbreak of Fascism," The Historian, 45:3, May1983, pp. 324-336. Available on JSTOR.)

October 1920 can be seen as the peak of socialist power in the province of Ferrara.

The Fascists Show Up

The long climb up was followed by a swift slide down. In the elections of May 1921, a little more than six months after the communal elections in October 1920, it was the fascists who were on the winning side.

How did the fascists pull this off? It's hard to overestimate the importance of lying and violence.

Here are the mechanics of what they did.

1. They stole mercilessly from the socialist playbook, most notably setting up labor exchanges to displace the ones maintained by the socialists.

2. They escalated the violence to levels just short of civil war. They were sadistic and blood-thirsty, displaying an almost orgiastic dedication to violence and humiliation.

3. They adopted a pro-worker program and then betrayed the workers in favor of the bosses, without ever admitting what they were doing. They just flat-out lied, posing as the friend and protector of the working man when they were actually doing the bosses' bidding.

One more word on the violence of fascism. Bloodlust has been with us forever, but in the early twentieth century it actually gained a certain intellectual respectability. Preeminent in this particular sphere of lunacy were the Frenchman Georges Sorel and two Italians: the futurist Filippo Marinetti and the poet-demagogue Gabriele D'Annunzio, "whose achievement," notes Payne, "is sometimes said to have been to make violence seem erotic." (See Payne, pp. 28, 62-64. For more on D'Annunzio, see Lucy Hughes-Hallett, Gabriele D'Annunzio: Poet, Seducer, and Preacher of War, 2013.)

Fascism built on this base, as did others.

When we look back to the violence that the socialists deployed during the biennio rosso, I think it's fair to say the socialists were simply unprepared for the level of violence that the fascists brought to Ferrara. And the man who brought that violence was Italo Balbo.

Italo Balbo and Benito Mussolini

How important was Italo Balbo? Let's have a brief look at how things had been going for the fascists.

Fascism did not come from nowhere; it came from socialism, by way of World War I. Benito Mussolini was himself a committed socialist who had spent time in jail for his organizing activities. He also worked as a journalist and rose to become the editor of the socialist newspaper Avanti.

The Italian socialist party was opposed to World War I. Mussolini, however, found that he was strongly in favor of Italy joining the war on the side of the British and the French. The Italian socialist party expelled Mussolini, who joined the army and was injured in a training mishap.

|

| Mussolini as bersagliere. |

After the war Mussolini and a small group of others formed a new political party in Milan. The first meeting took place at the Piazza San Sepulcro on March 23, 1919. (Payne, p. 90.) The group included a number of veterans, including former members of the arditi, specialized assault troops typically drawn from the ranks of the elite bersaglieri and alpini.

The arditi were the hard core of the fascist squadri, small groups formed for intimidation, enforcement, and street fighting. And there was scrapping in Milan. On April 15, 1919, a group mainly composed of arditi attacked a socialist demonstration and then went on to burn the offices of the socialist newspaper Avanti. Three people were killed. (Payne, pp. 91-92.)

In the November 1919 election the fascists drew 4,657 votes in Milan from an electorate of 270,000. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 75.) Nationally, they ran 19 candidates and managed to elect one deputy, from Genoa. (Payne, p. 93.)

It might be an exaggeration to say the fascists were basically dead in the water going into 2020. But then, maybe not. According to the records of the Milan central committee, at the end of 1919 the party had only 870 members scattered across Italy. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 69.)

Meanwhile, in Ferrara, attempts to establish a local branch of the party sputtered and failed through 1919 and well into 1920. Then, in September and October of 1920, a hard-working and remarkably persistent young man named Olao Gaggioli finally succeeded in forming a successful fascio. (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 55-57, 65-68, 106.)

(Fascio in Italian simply means a small group of people or bundle of things. There were quite a few fasci floating around Italian politics at this time - the futurists had one, for instance. Similarly, when Mussolini adopted the ancient Roman fasces in 1919, he was coopting an image that was well known in Italy as a symbol of unity and very soon acquired the useful meaning of "unity by means of authority," one of the basic messages of Italian fascism. For more on the fasces, see T. Corey Brennan, The Fasces: A History of Ancient Rome's Most Dangerous Political Symbol, 2023, chapter 11.)

The previous state of inanition demonstrated by fascism in Ferrara was underlined when, in October 1920, the fascio in Ferrara asked the central committee in Milan to send along some membership cards. The central committee replied that it had no record of the formation of a fascio in Ferrara and therefore could not send along membership cards. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 106). Gaggioli managed to smooth over this bump in the road and get his membership cards.

The October 1920 election was, as we have seen, a blowout victory for the socialists. "Paradoxically," as Corner notes, "the elections were a triumph for the fascio." Although they had organized too late to have much effect on the outcome of the election, organize they did, handing out leaflets, talking to voters, setting up a public meeting, visiting polling places on election day, and - most saliently - organizing squadri. (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 111-112.)

After the election, violence escalated (there does seem to be a theme in this story of elections and labor contracts not settling anything). The peak of violence came on December 20, when fascists and socialists had it out in Ferrara's main square. Four people died on the scene, and a fifth died later in the hospital. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 117.)

People noticed. The landowners liked what they saw, particularly because the other parties had just shown themselves utterly incapable of mastering the socialists. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 107.) They particularly liked the squadri. However, they saw improvement opportunities, and soon the fascio found itself casting about for a better leader. They found him in Italo Balbo.

Balbo's critics argued that the landowners were responsible for Balbo's selection. "They wanted him to build the local fascio from an uncertain and unsavory gang of idealists and malcontents into a reliable instrument with which to destroy the socialist labor organizations." (Claudio Segre, Italo Balbo: A Fascist Life, 1987, p. 42.)

In mid-February, at the direction of the central committee in Milan, the local fascio appointed Italo Balbo as their leader, or segretario politico. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 132.)

During World War I, Balbo had served as a lieutenant in the alpini. Although technically not one of the arditi, who were formed into separate units, he did wind up commanding an assault platoon within an alpini battalion near the end of the war, and experienced some pretty intense combat. (Segre, pp. 22-27.)

Balbo initially thought of his new job as a temporary position. I suspect he may have assumed that the timing would be similar to that of a normal political campaign, and that the end point would be the May elections. So, before he said yes, there was a brief period of negotiation in which he demanded a follow-on job in a bank, after his work with the fascio was done. (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 171- 173; see also Segre, pp. 41-43.) He clearly did not foresee the fascio as a career, but rather as a stepping stone. That view changed quickly, as he developed a clearer understanding of the opportunities available in a very fluid situation. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 175.)

As leader of the fascio, Balbo essentially imposed a military rural pacification program on his own home. (He had been born in Quartesana, a suburb of the city of Ferrara, on June 5, 1896. Segre, p. 4.) The basic tactic in Ferrara was the punitive expedition. "Operating usually in fairly large numbers - often more than 100, sometimes as many as 500 - the fascists would descend on a rural centre at night, search out the most prominent socialists of the area and proceed to beat them up or kill them outright. In March, for example, three columns of more than 100 fascists each blocked all exits from Ro and systematically worked through the centre, beating up all those who offered resistance." (Corner, Ferrara, p. 139. Footnote omitted.)

One estimate is that, during February, March, and April 1921, there were more than 130 of these spedizioni punitive in Ferrara. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 139.)

The preparatory work in the first part of the year explains the success that the fascists had in the May 1921 elections. Prime Minister Giolitti decided to invite the fascists to join an existing alliance of parties known as the blocco nazionale. In the province of Ferrara, the socialists drew 16,967 votes (down from 43,726 in 1919), and the blocco drew 49,122 votes (up from 6,939 in 1919). And Benito Mussolini was elected to the chamber of deputies (the lower house of the Italian parliament) for the first time - representing Ferrara. (See Corner, Ferrara, pp. 179-181.)

Nationally, "Giolitti's attempt to utilize the fascists in order to weaken his opponents was a total failure ... it served only to give prominence and a certain respectability to the fascists, who gained thirty-five seats in the new parliament." (Corner, Ferrara, p. 181.)

Italo Balbo, still in his twenties, found that he was one the most prominent figures in the province of Ferrara. He controlled the fascist party, controlled the squadri, "and had become a figure of considerable importance in the eyes of the fascist Central Committee." (Corner, Ferrara, p. 183.) This made him the ras of Ferrara. And a brilliant future awaited him.

(Ras, in fascist usage, means party boss. It derives from an Ethiopian term for a senior leader. Many Italians of this era were fascinated by the world south of the Mediterranean, perhaps as a result of Italy's many imperial adventures and misadventures in northern Africa, dating back to the nineteenth century.)

What happened in Ferrara was important. As Corner puts it, "it was in Ferrara in early 1921 that the potential of fascism was fully demonstrated." (Corner, Ferrara, p. 137.) "The example of Ferrara, previously considered one of the impregnable strongholds of socialism, served to convince many still confused or uncertain about the intentions of fascism. It was what the fascists had done in Ferrara rather than what had been said or written in Milan that removed doubts and demonstrated the potential of fascism to such people." (Corner, Ferrara, p. 121.)

And so Mussolini, who had been bobbing about like a cork near the top of all this ferment, finally found his feet with the elections of May 1921. Is it too much to say that those feet were provided by Italo Balbo? Perhaps. But Balbo wasn't done. In fact, he was just getting started.

|

| Italo Balbo. |

And Then ...

Again, after an election, we see the level of violence not decreasing, but increasing. Even before the election, Balbo had not confined his activities to the province of Ferrara, most notably appearing in Venice in April. (Segre, pp. 53-55.) Then, in June and July, the government noted the appearance of squads from Ferrara in Venice, once again, and in Ravenna. (Corner, Ferrara, p. 183.)

Balbo was clearly building an army step by step. Starting with company and battalion size groups drawn from the one province of Ferrara, he was soon thinking on a much larger scale. In September he led a regiment of about 3,000, drawn from Ferrara and Bologna, back to Ravenna. (Segre, pp. 62, 65.) By January 1922, Balbo had been officially put in charge of the squads in provinces along the Adriatic coast, extending north beyond Veneto, south as far as Le Marche, and inland to Mantua. (Corner, Ferrara, p, 200.)

In May1922 he held something of a reunion in the city of Ferrara, with 40,000 squadristi and farm workers attending. Its purpose was to intimidate local government officials, and it clearly succeeded. (Corner, Ferrara, pp. 215, 217, 218. Today a typical U.S. army corps, composed of several divisions, would be about the size of the force that Balbo deployed in Ferrara.)

Ravenna did not submit easily to the fascist yoke, and so Balbo found himself back there in July of 1922. Before the battle was fully joined, the political parties in Rome agreed to a peace pact. Balbo said he would honor the pact, but doubted that it would hold. And it didn't. When a fascist was shot and killed while walking in a working-class neighborhood, Balbo and his squadristi responded by burning headquarters belonging to the socialists, the communists, and the anarchists. Italian troops in the town, including two armored cars and a detachment of cavalry, stood by.

Balbo then decided to take his show on the road. He went to the police chief. "I announced that I would burn down and destroy the houses of all socialists in Ravenna if within half an hour he did not give me the means required for transporting the fascists elsewhere. It was a dramatic moment. I demanded a whole fleet of trucks. The police officers completely lost their heads, but after half an hour they told us where we could find trucks already filled with gasoline. Some of them actually belonged to the office of the chief of police."

Over the next 24 hours, the fascists swept through the provinces of Ravenna and Forli, burning socialist and communist headquarters as they went. Balbo again: "Huge columns of fire and smoke marked our passage. The entire plain of the Romagna all the way up to the hills was subjected to the exasperated reprisal of the fascists, who had decided to end the red terror once and for all." (For the July 1922 expedition to Ravenna, and the subsequent Column of Fire, see Segre, pp. 86-87.)

The Column of Fire was Balbo's finest concerto of suppression. But there was a much larger work coming in October 1922 - a symphony called The March on Rome. This was not a combat operation. It was a promenade militaire that made a show of intimidation and provided a plausible excuse for people to do what they already wanted to do. Which was to put Mussolini in the nation's driver's seat.

Balbo was one of the four men - the quadrumviri - who actually organized and commanded this operation. (See Segre, chapter 5.) The result was that the king appointed Mussolini prime minister; Mussolini used that post to establish a totalitarian dictatorship in Italy. (He continued to hold the title of prime minister until 1943, when the fascist regime collapsed.)

Balbo went on to become head of the Italian air force and, later, governor-general of Libya. When Mussolini declared war on Britain and France on June 10, 1940, Balbo was in command of the Italian forces opposing the British in Libya. On June 28, 1940, he was killed in a friendly-fire incident while his plane was trying to land in Tobruk. He was 44 years old. (Segre, p. 3.)

Demagogues Don't Deliver

A while ago, I wrote a story about demagogues, noting that things often don't end well for them, and that things often don't go well for their constituents, either. (To see the story, click here.)

Paul Corner, in his Mussolini in Myth and Memory, does an excellent job of cataloguing how things didn't go very well for many people in fascist Italy. "It is worth noting that, while Italian wage levels had risen continuously in the decade before the First World War, international comparisons show that Italy was the only European country with a consistently descending level of wages for the period 1920-1939." "By 1938 industrial workers were earning, in real terms, 20% less than they had earned at the beginning of 1923 - and they were working longer hours." As for farm workers, "Figures printed by the fascist union in Rovigo, for instance, show that, in 1931, labourers were earning only 60% of what they had been paid in 1921 (and this, given the source, was almost certainly an overestimation." (Corner, Mussolini, pp. 76-78. Rovigo is the province directly north of Ferrara.)

With less money, people ate less well. According to the International Labour Organization, "the population as a whole, surveyed in the period 1928-34, ate much less meat, eggs, butter, and very much less sugar, than the population in any other western European country (Spain and Portugal were not included)." Another study found that "people were eating fewer wheat-based products at the end of the 1930s than at the beginning of the 1920s." (Corner, Mussolini, p. 78.)

Pellagra is a disease of poverty and malnutrition. Between 1932 and 1939, the incidence of pellagra in Italy increased by a factor of ten. (Corner, Mussolini, p. 90.)

Not surprisingly, there was a large increase in male suicides between 1925 and 1935. (Corner, Mussolini, p. 65.)

So much for the thought that, under fascism, "we lived well."

Lessons for Us

If you look around the United States today, I don't think you'll have any trouble finding violence and lies. You might want to give some thought to how much of the violence is purposeful instead of a random result of our idiosyncrasies. However, the main thing I suggest you look at is the position of our elites relative to democracy. Are they for it or against it?

The basic problem in Italy was not the fascists, it was the elites. And I think the same is true in the United States today.

I'm not concerned about the military, so far. I am concerned about the judiciary, and I'm downright worried about the police. On the other hand, the federal bureaucracy is called the deep state because it believes in democracy.

As for the fifty states, they are split, with red states tilting toward theocratic fascism.

I'm not concerned about the pope right now, but I am concerned about his bishops. And I think the evangelicals want to go back to the days of the witch trials in Massachusetts.

I think business and the legal profession are split, and the same goes for organized labor. (Think police unions, among others.) As for the media, does Rupert Murdoch believe in democracy, or does he believe in oligarchy facilitated by fascism? Many rich Italians had hoped for this outcome, and I suspect quite a few American plutocrats feel the same way.

Education? A mixed bag. John Dewey would not be impressed. Do we teach our children to think for themselves and work together for the common good? Or do we teach them that every human interaction is a battle, and to the winner go the spoils?

Fascism has many friends in high places, including Congress, but not, right now, in the White House.

Let us go then, you and I ...

|

| Italo Balbo marching with Mussolini in 1923. |

To the best of my knowledge, all of the photographs here are in the public domain.

I've had to leave a lot out in this story. The underlying history is extremely complex. There were, for example, fascists who believed in helping the people. Mussolini himself was, from time to time, one of them. And the 1921 fascist program for agrarian reform was, at least superficially, very attractive, although in the end it was simply a snare for the unwary. For a bit more on these points, see Corner, Ferrara, pp. 146-151, 167-168.

See also Fascism, Jim Crow Was a Failed State, The Real Parallels Are With Weimar, On Demagogues, Greed Is Not Good, Narcissism and Dictatorship, How the Ship Sinks.

No comments:

Post a Comment