The Centers for Disease Control estimates that, in the 1918-1919 influenza epidemic, approximately 675,000 people died in the United States. In 1920, the U.S. population was 106 million. In 2020 it is 331 million - three times the 1920 number. So if we want to see how the 1918-1919 flu would have played out with today's population, we need to multiply by three, which gets us to a little over 2 million.

In 2018, a total of 2.8 million people died in the United States. This is all deaths, from all causes.

If the coronavirus turns out to be as bad as the 1918-1919 flu, we can expect total deaths to increase by 2 million, an increase of roughly 70 percent.

I'm putting these rather horrifying numbers out because, after President Trump's performance on Wednesday, I no longer trust what the federal government is telling the American people about the coronavirus.

(For an interesting Smithsonian article on disinformation during the 1918-1919 flu epidemic, click here.)

Friday, February 28, 2020

Monday, February 17, 2020

Springsteen's Bill of Rights

No Room for Summer Soldiers and Sunshine Patriots

Bruce Springsteen stands in a long line of people who have created and supported what used to be called the liberal consensus - now in dire jeopardy. Here's how he comes at it in his 2016 autobiography, Born to Run:

"I wanted to understand. What were the social forces that held my parents' lives in check? Why was it so hard? In my search I would blur the lines between the personal and psychological factors that made my father's life so difficult and the political issues that kept a tight clamp on working-class lives across the United States. I had to start somewhere. For my parents' troubled lives I was determined to be the enlightened, compassionate voice of reason and revenge. This first came to fruition in Darkness on the Edge of Town. It was after my success, my "freedom," that I began to seriously delve into these issues. I don't know if it was the survivor's guilt of finally being able to escape the confines of my small-town existence or if, as on the battlefield, in America we're not supposed to leave anybody behind. In a country this rich, it isn't right. A dignified decent living is not too much to ask. Where you take it from there is up to you but that much should be a birthright." (Pp. 264-265.)

In his State of the Union Message on January 11, 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approached the same ideas in a few paragraphs that have been called the Second Bill of Rights, or the Economic Bill of Rights:

"The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

"The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

"The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

"The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

"The right of every family to a decent home;

"The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

"The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

"The right to a good education."

(For the full text of this part of the speech, click here.)

As I mentioned before, these ideas, which have been widely accepted since I was a child and still are widely accepted by many people, including quite a few who are unwittingly fighting against them, are now in great peril.

This will be the year that decides our future. That future is in our hands. We must not fail.

|

| Ben Shahn, circa 1946. |

Bruce Springsteen stands in a long line of people who have created and supported what used to be called the liberal consensus - now in dire jeopardy. Here's how he comes at it in his 2016 autobiography, Born to Run:

"I wanted to understand. What were the social forces that held my parents' lives in check? Why was it so hard? In my search I would blur the lines between the personal and psychological factors that made my father's life so difficult and the political issues that kept a tight clamp on working-class lives across the United States. I had to start somewhere. For my parents' troubled lives I was determined to be the enlightened, compassionate voice of reason and revenge. This first came to fruition in Darkness on the Edge of Town. It was after my success, my "freedom," that I began to seriously delve into these issues. I don't know if it was the survivor's guilt of finally being able to escape the confines of my small-town existence or if, as on the battlefield, in America we're not supposed to leave anybody behind. In a country this rich, it isn't right. A dignified decent living is not too much to ask. Where you take it from there is up to you but that much should be a birthright." (Pp. 264-265.)

In his State of the Union Message on January 11, 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approached the same ideas in a few paragraphs that have been called the Second Bill of Rights, or the Economic Bill of Rights:

"The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the nation;

"The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

"The right of every farmer to raise and sell his products at a return which will give him and his family a decent living;

"The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

"The right of every family to a decent home;

"The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

"The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age, sickness, accident, and unemployment;

"The right to a good education."

(For the full text of this part of the speech, click here.)

As I mentioned before, these ideas, which have been widely accepted since I was a child and still are widely accepted by many people, including quite a few who are unwittingly fighting against them, are now in great peril.

This will be the year that decides our future. That future is in our hands. We must not fail.

Monday, February 10, 2020

I'm Haunted by Ben Shahn

The Faces, the Faces

Ben Shahn is known more for his murals than for his photographs, but his photographs for the Farm Security Administration in the 1930s are what draw me most to him. Shahn's FSA file contains a bit under 3,000 pictures. Some are missed shots (not surprising with the close-in, fast-moving situations he frequently sought out); many are simply documentary (this is what he was being paid to do); and a few are brilliant, in my opinion.

I finally broke down and went through the whole file. Here are my eleven picks. These images speak to me, and connect me vividly with a world that, from today's vantage, seems almost impossibly remote.

It is the world of the Great Depression. There is fear, and anxiety, and, especially among the children, surprising joy in simply being alive. And there is steadfast courage, lying just below the surface.

Shahn was not alone in doing this work. The photographers of the FSA were an amazingly talented bunch; the FSA photo project's most famous photograph is undoubtedly Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother (1936). And then there's Walker Evans, and Russell Lee. I love them all, but I feel a special attachment to Shahn.

I think it's partly because he is so free with his camera - horizons tilt, body parts are unexpectedly cut off; juxtapositions are odd but often beautiful; overlays are just part of the game. Balance is out; asymmetry is too calm a word for what is going on. There's more to it, though. The best of his work creates very sensitive portraits of real people who are not necessarily having their best day, and then delivers them in a cacophonous package that is in fact a very strong piece of graphic art.

Further Reading

The FSA website has a good essay on Shahn. To see it, click here.

The Library of Congress has also produced a book: The Photographs of Ben Shahn (2008). This volume contains 50 photographs and an interesting introduction by Timothy Egan.

For a very thorough appreciation of Shahn's work as a photographer, including his technique and sources of inspiration, and the relationships between his photographs and his paintings, with particular focus on his early photographic work in New York City, see Deborah Martin Kao, Laura Katzman, and Jenna Webster, Ben Shahn's New York: The Photography of Modern Times (2000).

Here's a good biography: Howard Greenfeld, Ben Shahn: An Artist's Life (1998).

|

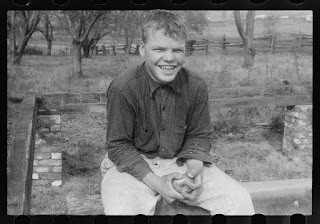

| Waiting for dinner bell, harvest time, Ohio, Ben Shahn/FSA, Aug. 1938. |

Ben Shahn is known more for his murals than for his photographs, but his photographs for the Farm Security Administration in the 1930s are what draw me most to him. Shahn's FSA file contains a bit under 3,000 pictures. Some are missed shots (not surprising with the close-in, fast-moving situations he frequently sought out); many are simply documentary (this is what he was being paid to do); and a few are brilliant, in my opinion.

I finally broke down and went through the whole file. Here are my eleven picks. These images speak to me, and connect me vividly with a world that, from today's vantage, seems almost impossibly remote.

It is the world of the Great Depression. There is fear, and anxiety, and, especially among the children, surprising joy in simply being alive. And there is steadfast courage, lying just below the surface.

Shahn was not alone in doing this work. The photographers of the FSA were an amazingly talented bunch; the FSA photo project's most famous photograph is undoubtedly Dorothea Lange's Migrant Mother (1936). And then there's Walker Evans, and Russell Lee. I love them all, but I feel a special attachment to Shahn.

I think it's partly because he is so free with his camera - horizons tilt, body parts are unexpectedly cut off; juxtapositions are odd but often beautiful; overlays are just part of the game. Balance is out; asymmetry is too calm a word for what is going on. There's more to it, though. The best of his work creates very sensitive portraits of real people who are not necessarily having their best day, and then delivers them in a cacophonous package that is in fact a very strong piece of graphic art.

|

| Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. Ben Shahn/FSA, perhaps Nov. 1941. |

|

| Crippled miner, Westmoreland County, Pa. Ben Shahn/FSA, Oct. 1935. |

|

| Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. Ben Shahn/FSA, perhaps Nov. 1941. |

|

| Cotton pickers, 6:30 a.m., Arkansas. Ben Shahn/FSA, Oct. 1935. |

|

| Schoolchildren, West Virginia. Ben Shahn/FSA, Oct. 1935. |

|

| Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. Ben Shahn/FSA, perhaps Nov. 1941. |

|

| Waiting outside relief station, Ohio. Ben Shahn/FSA, Aug. 1938. |

|

| Street musicians, Arkansas. Ben Shahn/FSA, Oct. 1935. |

|

| Harvest hand, Ohio. Ben Shahn/FSA, summer 1938. |

|

| Wheat harvest, Ohio. Ben Shahn/FSA, July-Aug. 1938. |

Further Reading

The FSA website has a good essay on Shahn. To see it, click here.

The Library of Congress has also produced a book: The Photographs of Ben Shahn (2008). This volume contains 50 photographs and an interesting introduction by Timothy Egan.

For a very thorough appreciation of Shahn's work as a photographer, including his technique and sources of inspiration, and the relationships between his photographs and his paintings, with particular focus on his early photographic work in New York City, see Deborah Martin Kao, Laura Katzman, and Jenna Webster, Ben Shahn's New York: The Photography of Modern Times (2000).

Here's a good biography: Howard Greenfeld, Ben Shahn: An Artist's Life (1998).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)